Building a Networked Key-Value-Store on an FPGA

This post is about building an FPGA based networked key-value-store in the functional hardware description language Clash. I’ll describe my FPGA-tailored hashtable design, the testing framework I built for it, and its performance and resource usage.

I also just think my design is kinda cool and novel so I want to share it with the world.

The source code for the top level project is available here and the Hashtable implementation is available here.

Background

A key-value-store (KVS), often implemented using a hashtable, is a database used for storing and retrieving data associated with a key. They are frequently used to cache data. Sometimes they run on the same machine as the client application. Sometimes they are accessed over the network. Software examples include Memcached and Redis.

If latency is important for your networked key-value-store, then it could run on an FPGA, or even an ASIC. Even with the fastest NICs available a round trip from the network to your CPU and back to the network takes ~700 nanoseconds. With FPGAs and 10G+ Ethernet we can cut out most of this latency and wire-to-wire response times <100ns are possible, but I don’t know if this kind of latency reduction is actually useful in practice. A major downside of using an FPGA, however, is much reduced storage capacity compared to a software implementation, especially if you are sticking with on-chip SRAM, as I am doing.

Platform

The platform I’m using is the Arty board (pictured above). It’s a tiny FPGA by modern standards and it only has 100M Ethernet so I’m not going to get <100ns latencies since the time to serialize a single packet is much longer than that at 100M. But, its sufficient to demonstrate a working key-value-store, and larger 10G+ capable FPGAs aren’t cheap.

Cuckoo hashing

Cuckoo hashing is an ingenious method by Pagh and Rodler for resolving collisions in a hashtable. Cuckoo hashtables have worst case constant lookup time. Not expected or amortized - worst case. Algorithms that take constant time are very well suited to FPGAs. Furthermore, insertions succeed in expected constant time. Following hashtable probe sequences in FPGA firmware is annoying to say the least. And, any time something takes a variable amount of time you have to stall things and implement backpressure. With Cuckoo hashing, at least for lookups, all these problems go away.

Cuckoo hashing, in its basic form, uses two tables and two independent hash functions, one for each table. Each key has two possible locations - one in each table. When inserting a value, one of the hash functions is used at random. If there is already a value stored in that location in that hash function’s table, it is evicted and replaced by the value we are inserting. The value that was kicked out is then re-inserted iteratively. The process repeats until we don’t have an outstanding value to insert. Note that it is possible for insertion to fail, entering an infinite loop. However, if the table’s load factor is kept below a certain number, this becomes very unlikely. If that brief explanation was unclear, I recommend reading the example on the Wikipedia page.

Since any key can only live in one of two possible locations, we can perform a lookup in constant time by inspecting both of those locations. Furthermore, we can use separate block RAMs, and do the lookups in parallel. So lookups on the FPGA only cost a single cycle, or maybe two if you are pipelining the RAM read.

Design

We need to adapt the software algorithm for cuckoo hashtable lookups and inserts for digital logic. Digital logic has different trade-offs to software, most notably, massive parallelism is available and should be used where possible. This is particularly apparent with RAMs. FPGAs have many RAMs spread out through the chip, each of which can be accessed fully independently. So, you can do potentially hundreds of independent RAM operations every cycle.

Lookups

RAM read parallelism is immediately useful when implementing lookups. One downside of cuckoo hashtables in software is that multiple RAM reads are required, unless you happen to get lucky and find the key in the first table you look in. As an aside, I believe this is why data structures such as Robin Hood hashtables are often preferred. With those, you can usually get the value in one memory read burst.

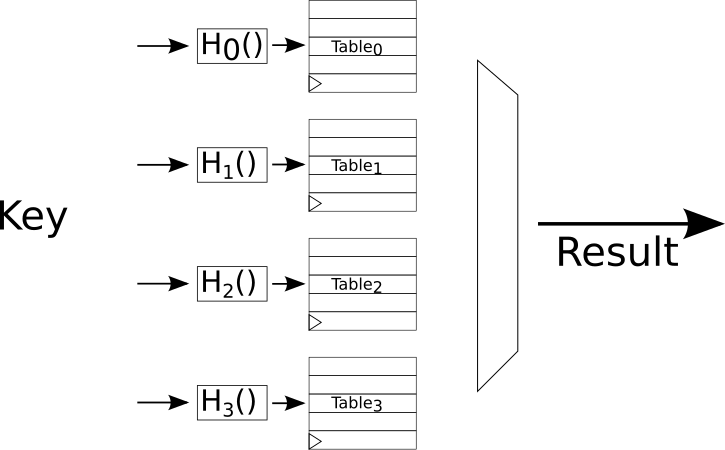

On an FPGA, unlike in software, these lookups can be performed in parallel. Since tables don’t have to be accessed sequentially, adding more tables is almost free on an FPGA. Cuckoo hashtables have the nice property that with more tables, higher load factors are possible. You can get >95% with only four tables. So, the number of tables trade off is greatly skewed towards higher numbers on an FPGA. I’ve found four to work well but much higher numbers would work too.

So, the lookup algorithm is trivial - compute the N hashes for each table and send the hashes to the RAM address ports. On the next cycle when the lookups are ready find the one (if any) that contained the key and select that. The logic is illustrated in the figure below. For a reasonable number of tables (64 or less?) this can all be done in one or two cycles depending on the RAM pipelining.

Inserts

Inserts are inherently more complex than lookups on an FPGA because we don’t get the constant time goodness that we get with lookups. Still, we want to exploit RAM parallelism as much as possible. The basic software algorithm tries inserting in any of the available locations for the key, if there is one free. If not, it kicks one out and repeats.

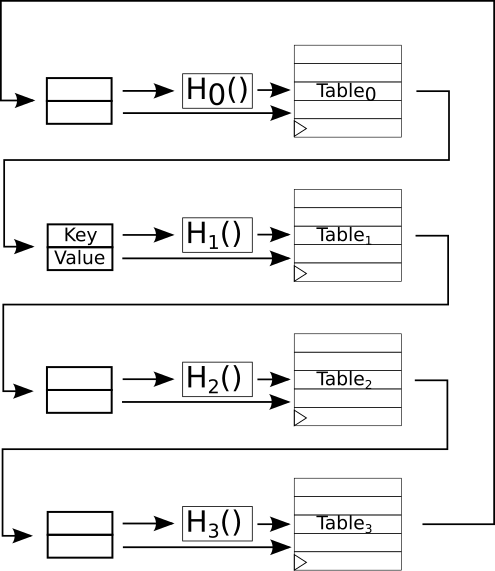

My FPGA algorithm, instead, gives the tables a fixed ordering. It inserts the value into the first table regardless of what is already stored in that location. It simultaneously reads out the value at that location (i.e. the RAM is operating in simple dual port mode). In the next cycle, when the write is complete and we get the read result, one of two things happen:

- It turns out nothing was stored at that location in the table, in which case we are done.

- There was a value at that location and it has now been evicted (because it was overwritten by the write in the previous cycle). We need to re-insert it in the next table in the fixed ordering.

The insertion process continues through later tables in the ordering until we hit the first case above and we insert without kicking something out.

The insertion process is shown in the figure below. Here we see the state of the system the cycle after the value to insert was written into the first table and the value at that location was kicked out. Note that there was a value at that location so it has been evicted and is awaiting inserting in the next table. Hopefully there will be nothing at H1(key) (the hash function) in table 1 and the insertion process will finish. Otherwise, another value will be evicted from table 1 and the process will continue.

Note that this has the very nice property that each RAM only talks to the RAM before it and the RAM after it in the ordering, so communication is local. This makes inserts scale well with the number of tables. Also note that evictions from the last table loop back around to the first. I like to call this a “cuckoo loop”. Basically, the evicted values keep bubbling around the loop until they are all settled.

Potential improvements

For simplicity, the current design only allows one insert outstanding and waits until that insert has been resolved before allowing future lookups. This means that you only have one eviction active at a time that bubbles its way around the cuckoo loop. This wastes a lot of RAM parallelism. It would be a reasonably straightforward extension of the design to allow multiple outstanding evictions at a time. You would have to be careful with forwarding though to make sure you forward outstanding evictions when lookups are performed. This would allow the design to handle a high rate of insertions, particularly if the number of tables is large. I plan to implement this in a future version.

Note that, in the current design, the insertion process can get stuck if you try to overfill the table. In practice I have found that this can be avoided by not filling the hashtable all the way to its expected load factor and stopping short by just a few percent. A more complete solution would detect when this happens and insert the currently outstanding evictions into a stash. At the bare minimum the logic could get the hashtable into an unstuck state and hand the evicted values that could not be re-inserted back to the logic that is using the hashtable.

You can also build a cache in this way. If inserts take too long, just drop the outstanding evictions at that point. This is like random cache eviction. You could add some kind of age counter to the table entries and terminate insertion when you encounter an entry with a sufficiently old age.

Top level

To give you a concrete idea of the hashtable’s functionality, here is it’s top level definition:

{- | Convenience wrapper for cuckooPipeline that checks whether keys are present before inserting them.

If found, it does a modification instead.

Only allows one insertion at a time so it is less efficient for inserts than `cuckooPipeline`

-}

cuckooPipelineInsert ::

forall dom m n numRamPipes k v.

HiddenClockResetEnable dom =>

KnownNat n =>

KnownNat m =>

(Eq k, NFDataX k) =>

NFDataX v =>

-- | Number of ram read pipeline stages

SNat numRamPipes ->

-- | Hash functions for each stage

Vec (m + 1) (k -> Unsigned n) ->

-- | Key to lookup, modify or insert

Signal dom k ->

-- | Modification command.

-- Nothing == no modification.

-- Just Nothing == delete.

-- Just (Just X) == insert or overwrite existing value at key

Signal dom (Maybe (Maybe v)) ->

-- | (Lookup result, Combined busy signal)

( Signal dom (Maybe v)

, Signal dom Bool

)

Notice the genericity of this function and how easily this can be expressed in Clash:

- They key and value datatypes are generic.

- The number of pipeline stages following the ram is configurable. This is important if you are building large hashtables spanning many block (of ultra) rams.

- The hash functions can be whatever you want and are passed in as function arguments representing combinational logic.

- The number of tables is generic.

- The size of the tables is generic.

FPGA network communications

All communication with the FPGA is performed over Ethernet. My Arty starter project provided the starting point for Ethernet communication. Commands are encapsulated in a simple UDP based protocol and there is simple logic written in Clash to decode and encode this protocol. To keep things simple, a common structure is used for inserts, lookups and deletes. A Haskell version of this structure is defined here. It consists of:

- The command (32 bits) (0 for lookup, 1 for insert, 2 for delete)

- The key (64 bits)

- The Value (64 bits) (for insertions, ignored for lookups and deletes)

The FPGA accepts any packets of the correct length. This can be error prone but my objective was to test the hashtable, not build a robust communications mechanism. It sends replies (for lookups) to hardcoded MAC and IP addresses, and a hardcoded port.

Testing

It’s easy to make mistakes when implementing a hashtable. There are corner cases and I can’t be confident that I have handled them without at least a comprehensive randomised testbench. One of the strengths of Clash is that every Clash design is also a valid Haskell program. This means that the entire Haskell testing ecosystem, including QuickCheck is available for testing Clash designs.

I also took the opportunity to play around with formal verification. I think the idea of exhaustively testing your design, or at least exhaustively testing it for a bounded number of cycles is very cool. I have a lot more confidence in my design now that I have run it through SymbiYosys.

Randomised QuickCheck simulations

I used the excellent QuickCheck library to generate a large number of random testcases and simulate my design on them. You can find the testbench here.

The testbench is composed of three separate operations each explained below:

- The design under test (DUT), i.e. the hashtable

- The testcase generator

- The test harness, which instantiates the DUT and feeds it testcases

Decoupling the test harness from the testcase generator means that, if we want to exercise some corner case, we only need to write a new testcase generator.

Operations

Each testcase consists of an operation for the hashtable to perform, and, possibly, an expected result. The Operation type is defined as:

data Op key

= Lookup key (Maybe String) -- (1)

| Insert key String -- (2)

| Delete key -- (3)

| Idle -- (4)

That is, in each cycle, we are either:

- Looking up a key, in which case we also expect a result: a

Maybe String, or, - Inserting a key value pair, or,

- Deleting a key and associated value, or,

- Doing nothing

Testcase generator

We need to generate a list of test operations and expected results to feed to the test harness. Generating a good distribution of operations is critical for getting good test coverage. This is handled by the genOps function, which I’ll take a moment to describe.

genOps returns a QuickCheck Gen object which encapsulates a list of test operations and expected results. During generation, it keeps its own mirror of the hashtable contents (as a golden model) so that it can know the current expected state of the hashtable. It randomly decides between creating a lookup, insert, delete, or idle operation.

For lookup operations, it non-deterministically chooses between looking up a completely random key (that is unlikely to be in the hashtable), or one that it knows to be in the hashtable (by looking at the set of keys in its mirror).

For insert and delete operations, genOps also decides non-deterministically whether to operate on an existing key or not. These operations don’t place have any requirements on the output of the hashtable but they do add key-value pairs to the mirror table to that subsequent lookups may require to be present.

These tests are useful for checking that the cuckoo hashtable achieves the theoretically expected load factor. We load the table up with a set number of key-value pairs before running the tests. The fact that we are able to load these values into the hashtable and read them back later in the test demonstrates that the table achieves the expected load factor.

Test harness

The test harness takes a list of operations to perform, instantiates, and simulates the cuckoo hashtable. It feeds the operations to the design under test (DUT) one by one, checking that the table’s outputs match the expected value for lookup operations. If it gets to the end of the list and all lookups have matched the expected results, the test has succeeded.

This directed randomised testing approach found many bugs that my initial hardcoded testcases missed, and no additional bugs were found during formal verification (below).

Formal verification

I also make use of bounded model checking to prove that my hashtable does the right thing, at least for a bounded number of cycles.

The excellent SymbiYosys verification flow compiles the Clash-generated verilog code and verilog assertions into a form that can be checked by SMT solvers. You can read all about this here.

Using a neat trick for verifying memories described in detail on Dan Gisselquist’s blog, I arbitrarily select a single key to monitor and generate arbitrary modification operations. Since the key was arbitrarily chosen in the first place, the property applies to all keys! The properties and scripts can all be found here.

Note that this isn’t a full proof of correctness. It states that for ~20 cycles (or however long the bounded model check runs before I get tired), for all possible behaviours of the environment, the design does the right thing. This is still quite a strong statement but it says nothing about what happens after those 20 cycles. To fully verify the design, a technique like k-induction is needed. I’ve played around with k-induction on some toy designs but it looks like it would be quite a lot of work to get it going here.

Real world tests

Even with all the testing so far, things can still go wrong - incorrect pin definitions, bad timing constraints, and compiler bugs (yes, this happens in FPGA land). So, I wrote some tests that exercise the whole system loaded onto the board in the real world. The tests are similar to but a bit simpler than the randomised simulation test above and can be found here.

There are two real world tests:

fillAndEmptywhich fills up the hashtable, reads everything back, deletes everything, then checks its empty.alternateInsertReadwhich alternately inserts keys and reads them back until the hashtable is full. Then, it alternately deletes items and checks they are no longer there until the hashtable is empty.

The design passes the tests and achieves the expected load factor in the real world.

Synthesis

Resource usage

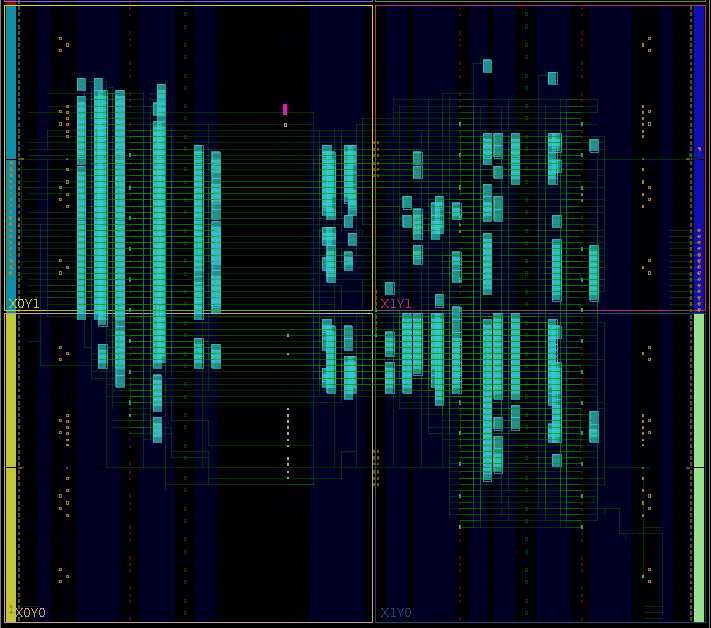

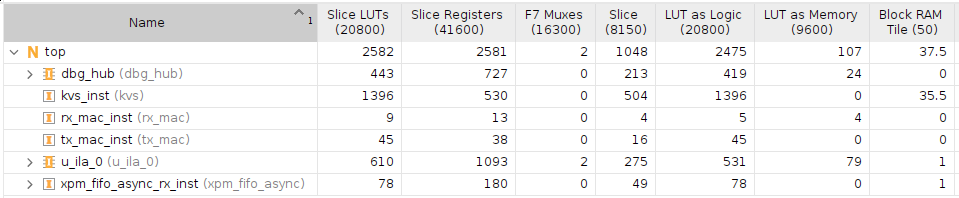

The utilization report can be seen in the screenshot below. LUT and flop resource usage is low as expected for a simple design. Block RAM usage is significant, where the number is exactly what I was expecting given the hashtable size.

Here’s a screenshot of the implemented design in Vivado because it looks cool:

And the utilization report:

Timing

Since I have used the slow 25MHz Ethernet clock, the design meets timing by a large margin. The greatest logic depth in the design is 12 levels. I am happy with this and it is about what I was expecting for a design without much pipelining. It will operate comfortably at much higher frequencies.

Latency

The latency of the actual hashtable in logic, from the key being valid to the data being ready is two cycles. This would have to be increased for larger hashtables on larger FPGAs. The actual wire to wire latency at the Ethernet level is much higher due the serialization delay at 100M. I’ll have to synthesize this for a 10G+ capable board one day and see how fast I can get it.

This post was discussed on Hacker News here.

An improved version of the hashtable in this post is described here.